OWNERSHIP: Taking Responsibility and Showing Initiative (2026)

You cannot teach a man anything; you can only help him to find it within himself.

~Galileo Galilei

Why did you become a mathematics teacher? Odds are that you found joy in the subject and wanted to share it with others. Perhaps it was because of the beauty found in a formula that explains why a phenomenon occurs in nature. Maybe you are curious and love to solve problems or puzzles. Or, you like the elegance in the language of mathematics and the certainty it brings. As educators, we would like to see a similar passion grow within our students for learning mathematics. Learning will take place when students take ownership in their own education - the second pillar of PROWESS.

To cultivate genuine interest in learning among students, it is essential that both faculty and students share a clear, mutual understanding of what learning entails. One valuable perspective views learning as both a process and a product—an individual, internal, and deeply personal endeavor. It is not something one person can do for another. As John Hattie (2009) points out, “It is students themselves, in the end, not teachers, who decide what students will learn.” This underscores the importance of understanding students’ thinking, their goals, and their reasons for engaging with the material presented in school.

Since learning resides within the individual, students must take ownership of their own learning journey (Milton, 1973). However, many students enter our classrooms holding misconceptions of what learning is. They often view it through a dualistic lens—believing that learning is simply about identifying right and wrong answers—rather than recognizing that knowledge can be contextual, relative, and open to interpretation (Perry, as cited in Thoma, 1993). Additionally, many students often rely on extrinsic motivators, such as grades or rewards, rather than cultivating an internal, intrinsic drive to learn. Several studies have shown that students driven by extrinsic motivation tend to achieve at lower levels than those who are intrinsically motivated (Lemos & Verissimo, 2014; Pulfrey, Buchs, & Butera, 2011). Furthermore, intrinsically motivated students are more likely to engage deeply with content, pursue learning to greater depths, and persist through challenges to completion (Stipek, 1993).

Creating an environment that is conducive to intrinsic motivation can instill student ownership, enhance greater learning, and enable long-term academic persistence.

Consider the contrasting stories of two students in a Beginning Algebra class. Both John and Lola enrolled in the class because it was required for their degree programs. John was promised a new car by his father if he completed the course with a grade of B or better. Lola, on the other hand, was a returning student with no such promise made to her. John dropped out of class before midterm whereas Lola completed the class with a grade of A. In this case, extrinsic motivation was not enough to encourage John to even do his homework. Lola understood the value of learning and completed her associate's degree.

As educators, our primary responsibility is to guide students toward intrinsic motivation—encouraging them to find value and satisfaction in the learning process itself, rather than relying on external rewards that may undermine genuine engagement. Research by Alfie Kohn emphasizes that extrinsic incentives can diminish intrinsic interest in tasks, highlighting the importance of fostering internal motivation (Kohn, 1993). To support this, faculty should actively cultivate inclusive and adaptable learning environments, participate in thoughtful course design, and engage in reflective practices that promote continuous improvement. Institutions and departments play a crucial role by providing necessary resources, professional development opportunities, and comprehensive assessment strategies to enhance teaching effectiveness and student success.

Before implementing these strategies, it's essential to establish clear expectations for students as learners, ensuring they understand their roles and responsibilities in the educational journey.

Student Ownership

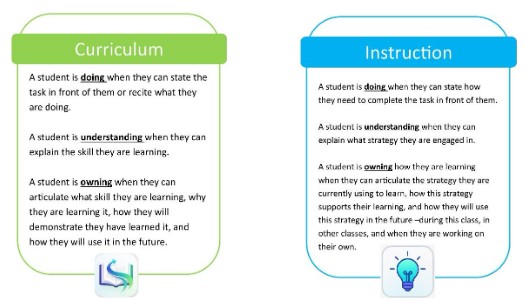

For a student’s education to be successful, the student must move from doing or understanding school to owning their learning. (Crowe, Kennedy, 2023). Summarizing what these means in terms of curriculum, instruction, assessment, and climate is as follows:

The best faculty who “achieve[ed] remarkable success in helping their students learn in ways that make a sustained, substantial, and positive influence on how those students think, act, and feel” (Bain, 2004, p. 5) do so by cultivating three components of student ownership of learning:

1. Discovery. An ideal classroom is where students are active participants in formulating conjectures, developing strategies for solving a problem, engaging in investigative tasks, or analyzing data. It is through these guided investigations that learning begins to take place.

2. Responsibilities. As students embark on the path of taking ownership of their learning, they encounter responsibilities that they may independently assume and others that require guidance. A clear understanding of course objectives and assessment criteria is essential for students to effectively direct their efforts. Engaging students in the development of respectful, inclusive, and transparent classroom norms fosters a positive educational environment .

When students take ownership of their learning, they become more engaged and contribute to a community characterized by mutual respect and shared learning. This dynamic is underpinned by a foundation of trust between students and faculty. Students trust that faculty will provide the necessary support to achieve course goals, while faculty trust that students will fulfill their responsibilities to meet those objectives. In this way, reciprocal trust transforms the classroom into a space where learners feel valued, supported, and empowered to contribute meaningfully to the learning community.

Arguably, the most important responsibility for the student is meaningful self-assessment. Students must recognize assessment as an integral component of the teaching-learning process and not just a means by which instructors assign a grade to their performance. Feedback garnered from a variety of assessments can help students better understand what constitutes an appropriate-and-complete response to a task and assist them to develop their confidence in performing self-assessments. The ability to assess one’s own work effectively is an important life skill, and of great value in the workplace.

Self-assessment is a process in which students reflect on the quality of their work, compare it to explicitly stated criteria, judge how well their work reflects the criteria, and make appropriate revisions. Also, it is a formative process that informs students about what part of their thinking and subsequent work require revisions and improvement. Some strategies (whether prompted by the instructor or initiated by the student) that students may use to develop effective self-assessment practices include

-

-

reflecting on prior knowledge and drawing from previous work to use/assist in new situations

-

using graphic organizers, which organize facts, concepts, ideas, or terms in a visual or diagrammatic way so that the relationship between the individual items is made clear

-

evaluating their own progress to recognize what they do and do not understand

-

using rubrics (when provided) to evaluate their progress during an assessment or activity.

3. Continued Learning. The goal of each student should be deep learning. As described in the book Deep Work (Cal Newport 2014 p 22), students will benefit by intentionally scheduling study blocks, reducing distractions, embracing boredom and taking breaks from social media. Signs that students achieve the goal of deep learning would be “that students developed multiple perspectives and the ability to think about their own thinking; that they tried to understand ideas for themselves; that they attempted to reason with the concepts and information they encountered, to use the material widely, and to relate it to previous experience and learning.” (Bain, 2004, p. 10). A student’s journey to meet this goal will encounter accomplishments as well as setbacks. Students need to be able to accept failure or mistakes as an important part of learning. As the entrepreneur Malcolm Forbes (1978) once said, “failure is success if we learn from it.” Recent studies have shown that when mistakes are made, the brain grows (Moser, Schroder, Heeter, Moran, & Lee, 2011). One type of response or spark observed in the brain is simply due to the conflict between a correct response and an error; it is not necessary that a person is aware that they have made a mistake. The second response is the reflection of the conscious attention to the mistake. According to Dweck (2006), people with growth mindsets have greater brain activity to follow mistakes. They understand that the path to success will have failures along the way and they are comfortable facing them, so long as there are opportunities to learn along the way. It is through persistence that brain growth occurs and learning takes place.

When students take initiative for their own learning, the results can sometimes have a positive ripple effect for other students as is demonstrated by Kyela’s story.

Kyela, a beautician pursuing her associate’s degree, enrolled in a basic math class as a result of her performance on the college’s placement test. She was understandably anxious about her math abilities, but she took ownership for her learning. As the semester progressed Kyela gradually took responsibility not only for her own learning but for that of the members of her group. Eventually she organized Sunday morning study sessions at the local coffee shop for anyone in the class to attend. As a result of her actions she achieved a grade of A in the course and the average grade in the class exceeded the average grade of the other sections of the same course that semester.

Faculty Fostering Student Ownership

In general, faculty should be working towards empowering students to take ownership of their learning by promoting self-regulated learning. Students should take control of and evaluate their own learning through the phases of task perception, goal setting and planning, implementation, and adaptation (Winne & Hadwin, 2008). Faculty should be guiding and engaging students in activities that foster discovery, responsibilities, and continued learning. According to Mortimer and Scott (2003), there are three tasks for the instructor in the student learning process:

Introduction of concepts - The instructor must be prepared to use a variety of ways to introduce a concept. The primary focus should be on fostering curiosity within the student. By providing students with open-ended questions or utilizing inquiry-based learning techniques, instructors are supporting the students’ intellectual need to understand a concept so that they are better motivated to learn it (Harel, 2013). If done correctly, students will be working on the discovery component of ownership.

Support for the development of meaning - The key word is “support”. Faculty must be patient, supportive, and available to help when students are frustrated or confused but still allow them to struggle and make mistakes. "Depriving some students of experiencing struggle robs them of valuable learning opportunities. All students deserve the right to struggle." (Productive math Struggle - SanGiovanni, Katt, Dykema 2020). It is vital that the instructor does not “do all of the heavy lifting” for the student. When students ask for help, a possible response is “let’s think about this for a minute… Do you want my brain to grow or do you want to grow your brain today” (Frazier, 2015, para. 13)? Faculty need to know when and how to intervene when work is headed in the wrong direction and be able to use good questioning techniques to redirect students rather than giving them immediate answers. Class activities should guide and direct them to begin to assume responsibility for their own learning. Students must have a variety of opportunities to develop confidence in their abilities.

When utilizing group work, faculty must make sure that it is not just a way to get work done faster, but that individual ownership is taking place. Consider Beth, an instructor who utilizes the flipped model of teaching, so she has opportunities every class period to take on a guiding role while students are engaged in group work. Her role has evolved over time as she has reevaluated what level of ownership the students have in the activities. Initially, her first semester of teaching was just spent answering questions, but in time she began to also do “interventions”. As she walked around the room, she pointed out possible errors in logic and asked groups to reexamine their thinking, thus encouraging group ownership. However, she realized that was not enough. Now, each semester she works at incorporating ideas that lead to individual ownership.

Provision of opportunity for transfer of ownership, practice, and application to student - The transfer of ownership to students happens in a variety of ways. To create a positive classroom climate for college students, it’s essential to start on the very first day by shaping their expectations. Involve students in setting clear, respectful, and inclusive ground rules to encourage a sense of ownership and mutual respect. Establish consistency in applying these expectations, while remaining flexible and open to feedback. This approach promotes fairness, fosters engagement, and helps build a supportive learning environment where all students feel valued and heard. By setting the tone early, instructors lay the foundation for a classroom culture rooted in trust, collaboration, and growth. Faculty can assist students to take ownership at the beginning of a course by allowing them to have a voice in how the course is structured. For example, Judy, a mathematics instructor, often involves students in the development of her course syllabi (Barkley, 2010). They determine aspects of the syllabus such as expectations and the consequences of not meeting those expectations when doing group work. She also affords them the opportunity to choose from a variety of learning activities that satisfy the course objectives.

Throughout a course, it is important that an instructor ensures that students understand the objectives of the course and are able to meet them. One example of how to achieve this is the method that Kevin uses in his classroom.

He has created a checklist of objectives for his students to use as a way to prepare for exams. After finding out (through surveys) that the students were not using them, he looked for other ways to enforce this idea. He made two changes to the checklist. In upper-level classes he added the words

“I can” at the beginning of each objective. He required students to look at the checklist at the end of each activity or class period to see where they stand. In his developmental courses, he has students reflect some more; they must check one of three statements for each objective as suggested by Boaler (2016):

- I can do this independently and explain my solution path(s) to my classmates or teacher.

- I can do this independently.

- I need more time. I need to see an example to help me (p. 152.)

Students hand in the checklist when they take the exam and are then required to reflect on their perception of their knowledge once the exams are handed back.

It is a faculty’s responsibility to design activities and assignments that will guide students to master course objectives. Students need to first try out and practice new ideas in familiar situations and then move to applying the knowledge to new and unfamiliar contexts (Mortimer & Scott, 2003). Students need to be presented with genuine application problems that require them to determine what technology, techniques, or methods to utilize and how to use them effectively. In an effort to improve success by engaging students in meaningful applications, a community college system in Florida contextualized their Intermediate Algebra and College Algebra courses. Business faculty were involved in the creation of real-world problems upon which the content was built. Mathematics faculty needed the support from business faculty to find realistic and meaningful applications. The success rate of students was 10% above those of students in courses not incorporating these problems.

Finally, providing a variety of assessments will help students recognize areas in their learning they need to improve. Feedback garnered from different assessment tasks is vital. Faculty should design structured reflection opportunities to help students assess their progress, adapt learning strategies, and take ownership of their growth. Instead of assigning endless homework problems, it may be more beneficial to ask students to answer some reflection questions, as suggested by Boaler (2016):

-

What was the big idea we worked on today?

-

What did I learn today?

-

What good ideas did I have today?

-

In what situations could I use the knowledge I learned today?

-

What questions do I have about today’s work?

-

What new ideas do I have that this lesson made me think about (p. 158)?

We illustrate these suggestions with an example from Barbra. She utilizes emoticons to have students gauge their understanding of a topic. Her quizzes begin with students choosing a smiley face, plain face, or sad face to indicate how they think they will perform. Next, they take the quiz and then indicate (with the same emoticons) their views of their performances. The entire class then goes over the quiz and students correct their work and make comments about what went wrong (or right). Afterwards, they use emoticons once more to indicate their actual performance. Students then write a few statements regarding what they need to do based on their results from the quiz. Most of the responsibility of the assessment is on the student, but Barbra does go over the quizzes and indicates mistakes students may have overlooked. She also praises them for their work and self-assessment as appropriate.

We illustrate these suggestions with an example from Barbra. She utilizes emoticons to have students gauge their understanding of a topic. Her quizzes begin with students choosing a smiley face, plain face, or sad face to indicate how they think they will perform. Next, they take the quiz and then indicate (with the same emoticons) their views of their performances. The entire class then goes over the quiz and students correct their work and make comments about what went wrong (or right). Afterwards, they use emoticons once more to indicate their actual performance. Students then write a few statements regarding what they need to do based on their results from the quiz. Most of the responsibility of the assessment is on the student, but Barbra does go over the quizzes and indicates mistakes students may have overlooked. She also praises them for their work and self-assessment as appropriate.

Faculty Ownership

We have taken a brief look at student ownership and ways in which faculty can guide students in the process. Now we focus on full and part-time faculty and how we can take ownership of our roles. When examining the faculty role in education, a large part involves the other pillars of PROWESS: mathematical proficiency, engagement, and student success. For this part of the discourse, we will examine three key areas in which faculty can take ownership: creating a safe and productive learning environment, taking an active role in course design, and becoming a reflective practitioner.

Learning Environment

The Learning Environment involves instruction and assessment practices intentionally developed to help all students achieve course (as well as individual) goals. It is a place where they experience mathematics with the guidance of faculty. While the word “classroom” is often used to refer to the learning environment, we prefer the broader term “learning environment” to include all settings in which faculty and students interact, including the online environment. First, looking more broadly at the idea of Powerful Learning Environments, Merrill (2020) summarizes five principles of learning environments that seem to be common in current instructional theories: Problem-Centered (learners are engaged in solving real-world/authentic problems), Activation (existing knowledge is activated as a foundation for new knowledge), Demonstration (new knowledge is demonstrated to the learner), Application (new knowledge is applied by the learner), and Integration (new knowledge is integrated into the learner's world).

To implement a powerful learning environment we suggest focusing on these four areas: method of instruction, teamwork, diversity, and learning outside of the classroom.

The method of instruction is a personal decision for faculty. Instructors should be aware of innovations in the area of instruction and be willing to adjust their methods as appropriate. Any strategy used should:

-

Engage students meaningfully with the material, keeping in mind their diverse learning needs.

-

Spark curiosity by incorporating thought-provoking content and activities.

-

Communicate topics and learning goals clearly to help students stay focused and motivated (Cai, Kaiser, Perry & Wong, 2009).

-

Center instruction around building true mastery of the intended learning outcomes.

-

Use purposeful questioning to encourage active participation and assess student understanding.

-

Integrate technology that aligns well with the learning objectives and enhances instruction.

-

Apply a variety of assessment methods to get a well-rounded view of student progress (Huba & Freed, 2000).

-

Offer low-stakes, formative and summative feedback that supports ongoing learning and growth.

-

Adapt instructional strategies as needed to ensure effectiveness for different teaching modalities

The second area of concentration, teamwork, is complex but vital. The ability to work in a team structure is among the most valued skills employers need when hiring new employees (Adams, 2014; Herrity, 2025: Wells, 2025). Facilitating successful teamwork requires not only training in specific techniques but also a clear rationale for the chosen approach to group work. Resources such as Building Thinking Classrooms (Liljedahl, 2021) offer research-based strategies for forming teams and for engaging the entire class as a single collaborative unit. In this model, knowledge flows freely among students, and mathematics itself—rather than the instructor—becomes the ultimate authority.

Based on work done by Johnson & Johnson (1999), when incorporating group work we suggest five aspects to focus on

-

Structure for positive interdependence: Group interaction is necessary for successful resolution of the question or task, and for linking individual success to the success of the group.

-

Structure for interaction: Group interactions include discussing solution paths, important concepts, and connections to prior knowledge, as well as facilitating help and words of encouragement when needed.

-

Structure individual accountability: Students are held accountable for their share of the work in the group.

-

Structure social skills: Group interaction requires interpersonal, social, and collaborative skills. Students must be provided guidance on how to effectively interact in a small group.

-

Structure group processing: Group members discuss effectiveness in reaching their goals and in working together.

The third area of concentration when designing a learning environment is diversity. Faculty must recognize that diversity manifests itself in a variety of ways: age, ancestry, color, disability, ethnicity, gender, gender identity or expression, genetic information, HIV/AIDS status, military status, citizenship status, national origin, pregnancy, race, religion, sex, sexual orientation, socio-economic status, or protected veteran status and academic preparation. To address issues related to diversity, faculty should

-

Set high expectations for all students and communicate them clearly to foster a culture of achievement (NCTM, 2000; Jamar & Pitts, 2005; CCCSE, 2008).

-

Apply proven instructional strategies to boost student success, such as using diagnostic assessments to identify and address learning gaps and incorporating varied teaching approaches (Holloway, 2004).

-

Actively support and encourage participation from underrepresented student groups to promote equity in the classroom.

-

Recognize and celebrate diverse languages and cultures as valuable assets to mathematical understanding, and highlight contributions from a variety of cultural backgrounds (Holloway, 2004; Ladson-Billings, 2021).

-

Guide students in locating and making the most of available academic support resources.

-

Partner with student support services to meet the individual needs of students with disabilities.

-

Be mindful that many students are balancing multiple responsibilities—such as work, family, and school—and offer encouragement and practical strategies to help them succeed.

-

Acknowledge the effects of math anxiety and provide students with tools and strategies to build self-confidence and reduce stress (Pajares, 1996).

-

Emphasize the critical role of math self-efficacy in student success by discussing its four key sources: mastery experiences, observing others, emotional states, and encouragement—while recognizing how these elements reinforce one another (Usher & Pajares, 2006, 2009).

-

Help students build confidence by creating opportunities for mastery experiences, recognizing that these are the most powerful predictors of self-efficacy. Strengthening foundational math skills can lay the groundwork for deeper learning (Usher & Pajares, 2006, 2009; Zientek, Fong, & Phelps, 2017).

The fourth area of concentration highlights the idea that the learning environment is not just what takes place inside the classroom, but also outside of the classroom. This encompasses a wide variety of considerations

-

Expect students to regularly engage with mathematics outside the classroom—this includes coming to class prepared and practicing skills introduced during lessons. Support these habits with timely, constructive feedback (Huba & Freed, 2000).

-

Promote meaningful interactions with and among students, both during and beyond class time, to build a supportive learning community.

-

Encourage students to explain mathematical concepts to peers and to communicate clearly with a range of audiences, from professionals to those without a technical background (Angelo, 1993; Huba & Freed, 2000).

-

Incorporate service-learning opportunities that allow students to apply their mathematical knowledge in real-world contexts.

-

Support and promote undergraduate research to deepen student engagement and exploration of mathematical ideas.

-

Be accessible outside of class to provide individualized support and guidance to students.

-

Take part in the planning and decision-making process for physical learning spaces—such as tutoring centers—that enhance mathematics instruction.

-

Recommend and help integrate appropriate technologies that enable students to explore and master mathematical concepts. Ensure that these tools are accessible and equitable for all learners.

Course Design

Most often, course design refers to the length, content, and structure of courses, but in this document, we will examine it in a broader sense to include components of instructional design. The goal of a good course design should be to foster student thinking. Decisions about course design should articulate how the curriculum is going to be delivered to students in ways that promote PROWESS. These decisions are best viewed as a joint responsibility by all faculty involved with a course, including a joint decision on ranges of acceptable variation between sections and delivery methods. We provide suggestions (in no particular order) for course design:

Course Design and Structure

-

Align Learning Outcomes Across Modalities. Ensure that the learning outcomes for online mathematics courses are aligned with those of their in-person counterparts, providing a consistent and high-quality learning experience for all students.

-

Offer Flexible Course Structures. Support diverse learning needs and paces by offering alternatives to traditional course formats—such as co-requisite models, accelerated options, or personalized learning pathways.

-

Support Diverse Teaching and Learning Styles. Encourage faculty to embrace a variety of teaching methods and design courses that incorporate multiple instructional approaches to reach and support all learners and design courses that include multiple means of representation, engagement, and expression.

-

Create Contextual and Interdisciplinary Assignments. Design tasks that connect mathematics to real-world scenarios and other fields of study, encouraging students to apply their skills in meaningful ways.

Student Learning and Engagement

-

Promote Student Self-Reflection. Incorporate assignments and feedback opportunities that help students reflect on their learning journey and take ownership of their academic progress.

-

Foster Development of Diverse Learning Skills. Offer resources and guidance that help students strengthen a broad set of learning strategies, from critical thinking to time management.

-

Address Student Misconceptions. Actively identify and clarify common misunderstandings to help students build a solid conceptual foundation in mathematics.

Assessment and Feedback

-

Ensure Inclusive and Accessible Assessment Practices. Develop assessments that are fair and inclusive, taking into account the diverse cultural backgrounds, abilities, and learning styles of all students (Ladson-Billings, 2021).

-

Incorporate Varied Assessment Techniques. Use a variety of assessment methods—including performance tasks, projects, interviews, and portfolios—alongside traditional exams to give a fuller picture of student understanding.

-

Use a Data-gathering Paradigm. Utilize observational and conversational data along with traditional assessment to assign grades instead of a traditional point-gathering paradigm. (Liljedahl, 2020).

Resources and Materials

Technology Integration

-

Integrate Technology to Support Learning Goals. Use technology purposefully to reinforce course objectives and help students meet learning outcomes across all modalities of instruction.

-

Employ Technology to Enhance Mathematical Thinking. Incorporate digital tools that support exploration—helping students discover patterns, test ideas, and build logical reasoning skills.

-

Ensure Technology Accessibility. Select technologies that are fully accessible to all students, including those with disabilities, to create an inclusive digital learning environment.

-

Provide Transferable Technology Tools. Offer students access to applications and tools they can continue to use in other courses and beyond the classroom, supporting long-term academic and career success.

Continuous improvement of course design can be achieved by using effective assessments in which faculty identify assessment tools linked to desired student learning outcomes and proceed through a four-step implementation cycle of planning, gathering relevant data and evidence, interpreting them, and using results to make informed instructional decisions. Instructors should participate in the development and assessment of not only individual courses but also how the courses contribute to general education outcomes in mathematics.

Becoming a Reflective Practitioner

Instrumental to faculty ownership is to be a reflective practitioner who examines curriculum and teaching practices to identify areas that need improvement. We offer suggestions for becoming a reflective practitioner

-

Reflect on whether students are actively taking ownership of their learning. This involves clearly defining what ownership looks like and identifying methods to assess it effectively.

-

Regularly review courses and curricula to identify areas for ongoing improvement and innovation.

-

Stay informed about current research in teaching and learning, and apply evidence-based practices to enhance course design and instruction.

-

Engage in continuous professional development to stay current with educational research, teaching strategies, and technological advancements that support effective instruction.

-

Explore and adopt emerging tools—such as artificial intelligence—to personalize learning, deliver timely feedback, and improve instructional efficiency, while upholding principles of equity and academic integrity.

-

Design and implement action research projects as a means of investigating and improving teaching practices.

-

Promote a growth mindset among students by creating environments that value effort, persistence, and learning from mistakes.

-

Use multiple perspectives to examine and improve teaching practices, including personal experiences as a learner, student feedback, peer observations, and insights from educational literature (Brookfield, 2002).

-

Contribute to a culture of collaboration and idea-sharing among faculty. This can be facilitated through departmental meetings where instructors rotate presenting on specific courses or teaching strategies. Additional professional growth opportunities include attending conferences or on IMPACT Live! or communities of practice.

Department and Institution Ownership

As full and part-time faculty take ownership of individual responsibilities for the learning environment, course design, curriculum, and assessment, it is the role of mathematics departments and institutions to support faculty in their teaching. By faculty uniting as a department, they are more likely to influence their institutions into listening to and acting upon the needs of the faculty. The institution needs to work with the faculty to determine the best course of action given the resources that can be made available.

One area that departments and institutions have the most influence over is in providing a supportive learning environment consisting of contemporary classrooms, mathematics tutoring labs, learning centers, counselors, and service for students with disabilities, to name a few. Learning environments should be adaptable to the needs and characteristics of students. Classroom layouts, which include furniture in the case of traditional settings, the design of virtual courses, and technology resources for both, all contribute to the learning of mathematics. As such, departments and institutions should

-

Provide the equipment and training faculty need to create engaging, effective classroom environments that support deep mathematical learning.

-

Ensure all students have access to essential technology—such as computers, software, calculators, digital recorders, and educational videos—to support their success.

-

Design both physical and virtual classrooms with accessibility in mind, following principles such as those outlined in Universal Design for Learning (CAST, 2011).

-

Promote and support effective instructional practices across all learning formats—face-to-face, online, and hybrid/blended classrooms.

-

Collaborate with faculty to make informed course placement decisions that best support student learning and success (AMATYC Position Statement).

-

Offer ongoing professional development for all faculty, with a focus on encouraging student ownership of the learning process.

-

Ensure faculty can engage in all phases of action research (planning, action, observation, and reflection, with the ultimate goal of improving teaching practices and student outcomes) to improve instruction.

Departments and institutions must create environments that nurture both academic learning and a strong sense of community. Learning centers should serve as inclusive and welcoming spaces where students not only receive academic support but also feel connected, encouraged, and valued. These centers play a vital role in fostering collaboration, peer interaction, and confidence-building—all of which contribute to student success. To promote this supportive atmosphere, departments and institutions should:

-

Provide adequate space and resources for peer and professional tutoring, as well as mathematics resource centers that invite collaboration and sustained engagement.

-

Set clear qualifications for tutors to ensure they are only supporting courses in which they have demonstrated proficiency, maintaining the integrity of academic support.

-

Establish robust training programs for mathematics tutors, peer leaders in supplemental instruction courses, and other student support staff to equip them with the skills needed to assist students effectively and empathetically.

-

Offer student-centered workshops that focus on essential academic and personal skills, including math-specific study strategies, managing math anxiety, and effective use of technology.

-

Ensure that learning resources and support services are accessible at a variety of times—including evenings and weekends—to meet the diverse scheduling needs of students.

Another area that departments and institutions have the most influence over is the instructional materials that faculty use in their classes. The purpose of mathematics courses and programs in college is to develop students’ mathematical proficiency with the intention of preparing them for other courses and the workplace. Departments and institutions must oversee curriculum development and assessment in mathematics courses and programs. They must ensure that decisions are based on the needs of the local student population but that results also align and agree with national trends and visions as well as curricula at transfer institutions.

A curriculum must be designed for today’s students and tomorrow’s society. It must effectively meet the needs of as many academic paths and disciplines as possible. In particular, attention should be paid to the influence of technology, research on student learning, mathematics content, and skills needed for successful careers and responsible citizenship. Thus, departments and institutions should

-

Collaborate with all faculty to define clear and meaningful learning outcomes for each course, while also engaging with external stakeholders—such as universities, employers, legislators, and national organizations—to ensure relevance and alignment.

-

Ensure that developmental mathematics and co-requisite courses include outcomes that build quantitative literacy, equipping students with essential skills for success in college-level coursework.

-

Promote cross-departmental collaboration to support consistent instruction and assessment of mathematics-related outcomes in non-mathematics courses.

-

Conduct regular reviews and updates of student learning outcomes to keep them responsive to changing educational and professional needs.

-

Review placement practices and prerequisite structures to ensure they align with course content and support student progress.

The next area in which departments and institutions must recognize their responsibility and role is in fostering and providing professional development opportunities by the establishment of an effective professional development program. Participation in professional development activities has a measurable impact on teaching. Keys to providing an effective professional development program include (Morley, Jamie & Zutes, Spring, n.d.)

-

Connection to Evaluations: Linking professional development to annual performance reviews helps keep it meaningful and ensures everyone stays on track and accountable.

-

Consistency and Flexibility: Programs should be consistently applied yet flexible enough to accommodate individual faculty needs and schedules.

-

Recognition and Rewards: Active participation in development activities should be acknowledged and rewarded to encourage engagement.

-

Collaborative Learning: Encouraging faculty with similar goals to participate in activities together fosters a collaborative learning environment.

-

Streamlined Processes: Utilize electronic forms and platforms to simplify documentation and tracking of development activities.

The final area that departments and institutions need to take ownership in is that of assessment. Curriculum assessment provides mathematics departments with data to make informed decisions about course content and student learning. It is an ongoing process by which a college or department assesses what mathematics students know at the end of their course or program. Results should be analyzed extensively and discussed, as well utilized to revise and improve curriculum and courses. Departments and institutions should use the characteristics of action research to facilitate the:

-

Alignment of department-wide assessment tools with clearly defined course outcomes to maintain consistency and focus.

-

Assessments of courses regularly to monitor student progress and instructional effectiveness.

-

Scheduling and carrying out periodic evaluations of learning outcomes across all mathematics courses to support continuous improvement.

-

Analysis of assessment results thoughtfully and use the insights to inform teaching strategies and enhance student learning experiences.

-

Maintenance of documentation of course-wide interventions to support reflection, track progress, and guide future improvements.

-

Review and update of the curriculum regularly to ensure that courses reflect current standards and the evolving needs of a modern mathematics program.

Working Together

Students entering two-year colleges bring with them a variety of ideas of what learning is and what their role is in order to be a successful student. Fostering a culture of shared responsibility and proactive engagement among faculty, staff, and institutional leaders is essential to creating meaningful change in mathematics education. By working collaboratively—supporting one another, setting clear expectations, implementing thoughtful practices, and embracing innovation—we can create inclusive, student-centered environments that promote academic success and personal growth. When each member of the educational community takes initiative and ownership, we build a stronger, more responsive program that benefits not only our students but also the broader institution and society.

|

Are you looking for ways to heighten your ownership of your role as a member of the mathematical community? Would you like to learn about more ways to foster ownership in your students? Do you already have great information or activities involving faculty or student ownership? Head to myAMATYC Crowe, Robert , & Kennedy, Jane (2023). Developing Student Ownership (2nd ed.). Elevated Achievement Group, Inc. and find innovations your colleagues are using or contribute innovations and ideas of your own.

|

References

Angelo, T. A. (1993). A teacher’s dozen. AAHE Bulletin, 45(8), 3-7.

Adams, S. (2014, Nov. 12). The 10 skills employers most want in 2015 graduates. Forbes. Retrieved

from https://www.forbes.com/sites/susanadams/2014/11/12/the-10-skills-employers-most-want-in-2015-graduates/#423a69162511

Bain, K. (2004). What the best college teachers do. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Barkley, E. F. (2010). Student engagement techniques A handbook for college faculty. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Boaler, J. (2016). Mathematical mindsets: Unleashing students’ potential through creative math, inspiring messages and innovative teaching. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Brookfield, S. (2002, Summer). Using the lenses of critically reflective teaching in the community college classroom. New Directions for Community Colleges, 2002(118), 31-38.

Cai, J., Kaiser, G., Perry, G., & Wong, N. Y. (2009). Effective mathematics teaching from teachers' perspectives. Sense Publishers.

CAST (2011). Universal design for learning guidelines version 2.0. Wakefield, MA: Author. Retrieved from http://www.udlcenter.org/sites/udlcenter.org/files/updateguidelines2_0.pdf

Center for Community College Student Engagement. (2008). Imagine success: Engaging entering students (2008 SENSE field test findings). Austin, TX: The University of Texas at Austin, Community College Leadership Program. Retrieved from http://www.ccsse.org/center/resources/docs/publications/SENSE_2008_National_Report.pdf

Crowe, Robert , & Kennedy, Jane (2023). Developing Student Ownership (2nd ed.). Elevated Achievement Group, Inc.

Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House Inc.

Forbes, M. S. (1978). The sayings of chairman Malcolm: The capitalist’s handbook. New York: NY: HarperCollins.

Frazier, L. (2015, February 25). To raise student achievement, North Clackamas schools add lessons in perseverance. Oregonian/OregonLive. Retrieved from http://www.oregonlive.com/education/index.ssf/2015/02/to_raise_student_achievement_n.html

Harel, G. (2013). Intellectual need. In K. Leatham (Ed.), Vital directions for mathematics education research(pp. 119-151). New York: Springer.

Herrity, J. (2025, March 3). 12 reasons why teamwork is important in the workplace. Indeed. https://www.indeed.com/career-advice/career-development/teamwork-important

Holloway, J. H. (2004). Closing the minority achievement gap in math. Educational Leadership, 61(5), 84.

Huba, M. E. & Freed, J. E. (2000) Learner-centered assessment on college campuses: Shifting the focus from teaching to learning. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Jamar, I. & Pitts, V. R. (2005). High expectations: A" how" of achieving equitable mathematics classrooms. Negro Educational Review, 56(2/3), 127.

Johnson, D. W. & Johnson, R. (1999). Learning together and alone: Cooperative, competitive, and individualistic learning (5th ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Kohn, A. (1993). Punished by rewards. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Ladson-Billings, G. (2021). Culturally relevant pedagogy: Asking a different question. Teachers College Press.

Lemos, M. S., & Verissimo, L. (2014). The relationship between intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation, and achievement, along elementary school. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 112, 930-938.

Liljedahl, P. (2021). Building thinking classrooms in mathematics, grades K–12: 14 teaching practices for enhancing learning. Corwin Mathematics.

Merrill, M. D. (2002). First principles of instruction. Education Technology, Research and Development, 50(3), 43–59.

Merrill, M. D. (2020). First principles of instruction (Revised ed.). Association for Educational Communications and Technology (AECT).

Milton, O. (1973). Alternatives to the traditional: How professors teach and how students learn. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Morley, J. & Zutes, S. (n.d.). Faculty professional development made easy, [Powerpoint].

retrieved on March 12, 2018 from http://educationdocbox.com/Homework_and_Study_Tips/69117737-Faculty-professional-development-made-easy.html#tab_1_1_1

Mortimer, E. & Scott, P. (2003). Meaning making in secondary science classrooms. Philadelphia: Open University Press.

Moser, J., Schroder, H. S., Heeter, C., Moran, T. P., & Lee, Y. H. (2011). Mind your errors: Evidence for a neural mechanism linking growth mindset to adaptive post error adjustments. Psychological Science, 22, 1484-1489.

National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. (2000). Principles and standards for school mathematics. Reston, VA: Author.

Pajares, F. (1996). Self-efficacy beliefs in academic settings. Review of Educational Research, 66(4), 543-578.

Pulfrey, C., Buchs, C., & Butera, F. (2011). Why grades engender performance-avoidance goals: The mediating role of autonomous motivation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 103(3), 683.

Stipek, D. J. (1993). Motivation to learn: Integrating theory and practice. (2nd ed.). New York: Pearson.

Thoma, G. A. (1993, Spring). The Perry framework and tactics for teaching critical thinking in economics. Journal of Economic Education, 24(2) 128-136.

Usher, E. L. & Pajares, F. (2006). Inviting confidence in school: Invitations as a critical source of the academic self-efficacy beliefs of entering middle school students. Journal of Invitational Theory and Practice, 12, 7-16.

Usher, E. L. & Pajares, F. (2009). Sources of self-efficacy in mathematics: A validation study. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 34(1), 89-101.

Wells, R. (2025, May 1). 7 in-demand skills you need to have in your resume in 2025. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/rachelwells/2025/05/01/7-in-demand-skills-you-need-to-have-in-your-resume-in-2025/

Winne, P. H. & Hadwin, A. F. (2008). The weave of motivation and self-regulated learning. In Schunk, D. H. & Zimmerman, B. J. (2008), Motivation and self-regulated learning: Theory, research, and application (pp. 297- 14). New York, NY: Routledge.

Zientek, L. R., Fong, C. J., & Phelps, J. M. (2017). Sources of self-efficacy of community college students enrolled in developmental mathematics. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 1-18.