INFUSING EQUITY AND INCLUSION IN THE MATHEMATICS CLASSROOM

A garden's beauty never lies in one flower.

~Matshona Dhlliwayo

College mathematics classrooms aspire to be a place where the pursuit of knowledge knows no bounds. Here, students from diverse backgrounds come together with unique dreams, abilities, and experiences. Within this crucible of learning, we find a microcosm of our society, rich in its diversity yet burdened by the disparities that often afflict it (U.S. DoE, 2016). In today’s twenty-first-century world, the demand for mathematical literacy and critical thinking skills is more crucial than ever (Rizki & Priatna, 2019), necessitating educators ensure accessibility for all. “The American Mathematical Association of Two-Year Colleges’ (AMATYC’s) core values acknowledge the rights of all students to have access to high quality mathematics education in ways that maximize their individual potential” (AMATYC, 2020, para. 1). Curriculum, pedagogy, and classroom interactions impact all students.

Faculty’s curricular decisions and pedagogy, including their individual interactions with students, can foster inclusive climates. Also, students report it is important that they see themselves reflected in the faculty and curriculum to which they are exposed to create a sense of belonging and inclusiveness. Research suggests that greater representation of underrepresented groups among faculty may increase students’ sense of academic validation. (U.S. DoE, 2016, p. 37)

The purpose of this chapter is to help students, faculty, and institutions prioritize the recognition and celebration of each student’s unique identity, including age, ancestry, color, disability, ethnicity, gender, gender identity or expression, genetic information, HIV/AIDS status, military status, citizenship status, national origin, pregnancy, race, religion, sex, sexual orientation, socio-economic status, or protected veteran status. This begins with creating an environment where everyone feels valued and understood, and that they belong. Faculty and staff need ongoing training and professional development opportunities around recognizing and addressing their own implicit biases, learning to assist students who experience stereotype threat and microaggressions, and learning how to recognize microaggressions and when and how to address them. In addition, faculty can foster diversity, inclusion, and a sense of belonging in college and in the mathematics classroom by engaging in teaching and learning methods, such as active and collaborative learning. Designing courses using elements of universal design can reduce the need for individualized accommodations and improve the learning experience of all students. Institutions should support faculty and staff in engaging in these activities, provide ample opportunities for training and professional development, and encourage an attitude of exploration with a willingness to question current policies and procedures and an openness to trying new strategies. AMATYC actively encourages the participation of all individuals in decision-making processes and activities, recognizing the importance of diverse voices and viewpoints. Every student is a valued and equal member of the classroom community. Together, we will uncover the power of mathematics as a tool for empowerment, social justice, and individual growth, setting the stage for a more equitable future for all within our college mathematics classrooms.

Sense of Belonging

Faculty who belong to historically marginalized groups may join a department or an organization, but without a sense of belonging may choose to move on. The same is true for students. Lewis et al. (2016) define academic belonging as “the extent to which individuals feel like a valued, accepted, and legitimate member in their academic domain” (p. xx) and go on to state, “Belonging has long been recognized as an innate human need and an important driver of physical and psychological well-being” (p. 421).This is particularly evident in the STEM disciplines, where the higher up the course is, the less diversity we see. A lack of sense of belonging is probably a significant factor in the underrepresentation of women in science (Lewis et al., 2016; Master & Meltzoff, 2020; Rainey et al., 2018). Mathematics is frequently perceived as a challenging subject and has been historically represented as a gatekeeper to STEM disciplines; there may be no discipline more in need of creating a strong sense of belonging for students and faculty than mathematics. Consider the following contrasting stories of two students in a precalculus course.

Takei is a student in his fourth week of a precalculus class. Takei’s class does a lot of group work, so he has gotten to know several classmates over the past four weeks as they have worked together on various assignments. At the start of the semester, Takei’s instructor had the class set ground rules for group work that included valuing all contributions and supporting one another’s learning. Takei’s instructor knows his name and acknowledges his contributions to class discussions in ways that leave him feeling motivated to learn more. Takei enjoys coming to class because it is a positive, comfortable environment.

Nichelle is also a student in her fourth week of precalculus class, but Nichelle’s class does not include assignments that encourage her to get to know her fellow students. As a first-semester dual enrollment student, Nichelle is not used to taking college classes and feels a little ill at ease. In the first week of class, the person next to her whispered “how stupid” under their breath as a student across the room offered an incorrect answer in a class discussion; this left Nichelle a bit afraid of what people might think of her contributions when she spoke up in class. Nichelle does not know of any other dual enrollment students in the course and has no reason to believe that the instructor knows her name. Nichelle feels anxiety going to class because she feels like an outsider in the environment.

Takei and Nichelle are at opposite ends of the spectrum on a sense of belonging scale. Sense of belonging means how much a person feels like they fit in and are part of a college community, which applies to instructors and students alike in different contexts. Belonging in a college community is fostered by feeling accepted, respected, included, and supported by others. From a student perspective, there are many ways in which faculty can support the development of a sense of belonging which will be addressed below.

Faculty perspective

On the classroom level, a student’s sense of belonging is integrally linked to the community environment, and faculty can make a difference in helping (or hurting) the student’s abilities to develop a sense of belonging. Four basic strategies for developing a sense of belonging in students include:

Educators play a pivotal role in shaping a sense of belonging in educational institutions, inside and outside of their classroom. By promoting empathy, acceptance, and mutual respect, faculty convey the importance of the other person. This sense of belonging, whether in students or with colleagues, contributes to increased engagement and a positive outlook towards the importance of their work. For students that can mean positive social and emotional development and increased academic success. For communities of faculty, we are helping to create more inclusive and equitable spaces, where we are enriched by the diversity of the people in our communities. A sense of belonging for faculty is just as important as it is for students, impacting educators’ professional efficacy, job satisfaction, and overall well-being. As colleagues, we need to attend to the ways in which we support one another and develop relationships within our communities (departments, institutions, and organizations).

Institutional perspective

At the institution level, faculty are at the heart of student success. They are directly responsible for curriculum development, delivering content, and connecting to students. Two-year college students face distinct challenges compared to their counterparts at four-year institutions, including limited on-campus living options, less involvement in college clubs, and greater non-education-related responsibilities, all of which leads to lower levels of belonging. It is the institution’s responsibility to support faculty with the opportunities and training to help them better develop curriculum and standard practices that elevate historically marginalized groups in the college community and in mathematics.

Finally, hiring is an important area for institutions to focus on. Research indicates that greater representation of underrepresented groups among faculty may increase students’ sense of academic validation. (U.S. DoE, 2016, p. 37) When the demographics of the faculty do not mirror the demographics of the community being served, students from underrepresented groups experience a lowered sense of belonging. This is a problem the institution should intentionally address. Students gain unique perspectives on mathematics, classroom interactions, college, and life from diverse identities. Diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility should be critical aspects of any hiring process, retention policy, professional development program, workload, and staffing policy.

A sense of belonging is deeply personal. No institution or single person can control whether another human feels like they belong somewhere, but we, individually and collectively, can make intentional choices to try to let others know they do belong and they are important.

Stereotype Threat, Implicit Bias, and Microaggressions

Most instructors go into the teaching profession because of a love for their discipline, coupled with a strong desire to help others or make a difference. However, barriers to their students’ success can be created by implicit biases, microaggressions, and stereotype threat. Unfortunately, many instructors have received little to no training in how to engage in such conversations, and the student may experience their awkwardness and hesitation as a microaggression. How do stereotype threat, implicit biases, and microaggressions affect the classroom dynamic and campus climate for faculty and students?

Stereotype Threat and Implicit Bias

Stereotype threat can preoccupy our students’ brains to the point that it reduces their focus and negatively impacts academic performance, leading to uncertainty about belonging in the mathematics classroom or even in college. Students may become hypervigilant, searching the environment for signs they do, or do not, belong, robbing them of cognitive resources that could be better employed in learning. When students are confident they belong, they focus better on the academic work, build better relationships, and engage more fully in the course and college.

Imelda is the only student who identifies as female in her calculus class. She is very conscious of being the only female and worries that every time she asks a question, other students and the instructor see her as the representative of all women.

To address stereotype threat, instructors should educate themselves about their own implicit biases. Education about and exposure to theories about both implicit bias and microaggressions can help faculty to recognize them when they occur and to then formulate appropriate actions. One of the most well-known instruments for assessing implicit biases is the Implicit Association Test hosted by Harvard, https://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/research/. There are 16 different tests on topics such as gender-career, transgender, disability, age, and race, which reveal the ease with which your brain makes associations. These can reveal biases towards associating White faces with good things and Black faces with negative things, for example. When faculty are tired, stressed, pressed for time, or have incomplete or ambiguous information about a situation, these biases can assert themselves. For example, an implicit belief that women are not good at mathematics may lead to seeing more errors in a woman’s work or in discounting the correctness of an argument. Situations that unexpectedly arise in the classroom can lead to these kinds of influences. Taking a moment to breathe and think can help faculty keep from being as influenced by implicit biases.

Addressing implicit biases and microaggressions is important work for faculty; these subtler forms of prejudice and bias may be more damaging to recipients than more overt forms of prejudice and bias (Solórzano et al., 2000; Sue, 2010), leading to disengagement, anxiety, frustration, self-doubt, symptoms of PTSD, and emotional distress (Casanova et al., 2018; Solórzano et al., 2000; Sue, 2010; Sue et al., 2007; Williams et al., 2020). Students who experience STEM-related stereotyping or biases may question whether they belong in a STEM field, doubt their own abilities, and ultimately choose not to pursue that path (Grossman & Porche, 2014). Consider the following methods to counteract implicit biases:

-

Meaningful interaction with people whose identities differ from one’s own (Staats, 2015/2016).

-

Exposure to counter-stereotypical examples, such as posters of Black or LGBTQ mathematicians.

-

Disaggregating success, failure, and withdrawal rates by race/ethnicity and/or gender.

Microaggressions

Individual implicit biases often underlie microaggressions, which draw attention away from the beliefs of the individual and, instead, focus it on the combined effects of many experiences and their connection to systemic injustice (Applebaum, 2019). The effect of microaggressions is cumulative; it can be compared to a thousand tiny stings or mosquito bites (Ogunyemi et al., 2020; Solórzano et al., 2000; Sue, 2010). Microaggressions include microassaults, microinsults, and microinvalidations (Sue et al., 2007).

Microaggression Examples

These “subtle snubs” (Sue et al., 2007, p. 273) are often dismissed or smoothed over as inconsequential, unintentional, and therefore undamaging, and harmless. In most cases, the perpetrator is interpreting the situation as a single instance, whereas the recipient is interpreting the situation as one of many experiences of a similar nature.

Bias in the classroom is more likely to be subtle than overt, and students generally perceive more bias than do instructors (Ogunyemi et al., 2020). The effect is often disengagement, frustration, and exhaustion, which can further damage academic performance (Sue et al., 2019). Students may end up feeling that they do not belong and that less is expected of them than of members of the dominant group. Microaggressions can come from all directions. Studies have shown that students tend to think that faculty of color are less competent and question their authority and grading schemes more frequently than faculty from dominant groups. This same dynamic applies to female faculty when compared to male faculty. To address bias in the classroom:

-

Directly confront bias, when appropriate.

-

Facilitate group conversation, validating the emotional responses of students.

-

Model “openness and honesty in discussing [one’s] own biases, weaknesses, or disruptive personal feelings” (Ogunyemi et al. 2020, p. 108).

There are various strategies to address microaggressions. Consider the following:

-

Confront the microaggression.

-

“I know you meant well, but that really hurts.”

-

“I know you meant it as a joke, but it really wasn’t funny.”

-

“I know you like to kid around a lot but think how your words affect others.”

-

“I know you meant it to be funny, but that stereotype is no joke” (Sue et al., 2019, p. 139).

-

Make the invisible visible.

-

“I don’t agree with what you just said.”

-

“That’s not how I view it” (Sue et al., 2019, p. 136).

-

“Are you saying that Black students are not good at problem solving?”

-

Disarm the microaggression.

-

Nonverbal communication: lifting your eyebrows, frowning, looking down or away, or shaking your head.

-

“Whoa, let’s not go there. Maybe we should focus on the task at hand” (Sue et al., 2019, p. 137).

-

Educate the perpetrator.

-

“I know you didn’t realize this, but that comment you made was demeaning to X because not all Arab Americans are a threat to national security.”

-

“I know you really care about representing everyone on campus and being a good X, but acting in this way really undermines your intentions to be inclusive” (Sue et al., 2019, p. 137).

-

“That is a negative stereotype of African Americans. Did you know they also want to be an engineer just like you? You should talk to them; you have a lot in common.”

-

Seek external reinforcement or support (Sue et al., 2019, p. 128).

One of the difficulties in addressing microaggressions is that a strategy might be effective and mitigate some of the negative effects for some groups (e.g., political activism for Latino/a students) and worsen the situation and effects for other groups (e.g., political activism for Black students) (Ogunyemi et al., 2020). Nevertheless, growing evidence suggests that more proactive strategies, such as problem solving and discussing the situation with supportive others, may help students better respond to future microaggressions. Disengaging, on the other hand, seems to have a negative effect (Ogunyemi et al., 2020, Sue et al., 2019). Consider the environment and context before deciding to act, so the situation is not inadvertently made worse for the victim. Constantly confronting microaggressions is emotionally exhausting and takes a physical toll:

-

Consider when and where (and whether) to confront the perpetrator.

-

Consider whether confrontation or education should be the more dominant response.

-

Be sensitive to the relationship dynamics among the people present.

-

Consider the ramifications and possible consequences of taking action, particularly when there is a power dynamic at play, such as between a student and faculty member.

When more people begin to accept collective responsibility to act, fear of negative consequences and retaliation will lessen, and real societal change can take place. (See also Chapter 6, p. 56.)

The world is a dangerous place to live, not because of the people who are evil, but because of the people who don’t do anything about it.

~Albert Einstein

The Institution’s Role in Equity

Colleges have continuously improved efforts to provide an environment that maximizes success and helps transform students’ lives. Developmental education reform efforts (Jenkins et al., 2019) and, more recently, guided pathway (AACC, 2017) efforts, have shifted the way institutions think about, support, and provide learning opportunities for students. As part of the guided pathways movement, the concept of meta-majors (Jobs for the Future, 2016), or areas of interest, has coincided with a shift away from a “single mathematics course for all” mindset and towards a mathematics pathway (Dana Center, n.d.) approach. By offering general education mathematics courses that align to students’ degree programs, faculty are creating learning environments that foster mathematical proficiency. Concurrently, developmental education reform movements have changed the path to these various gateway courses. Two primary changes, reduction of the developmental course sequence and adjustments to placement processes, enhance student access to and success in gateway mathematics courses. These and other continuous improvement efforts require institutional fortitude and resources to transform outdated practices. As institutions work and innovate to improve student success, efforts must emphasize equitable student success outcomes.

Institutions must ask themselves: How are we measuring reform movement success? Are outcome gaps being closed due to the new practice or policy? Are students experiencing support in equitable proportions? “We need a long-term sustained focus from professional organizations, college leadership, faculty, staff, and policy makers” (AMATYC, 2018, p. 62). However, supporting faculty and staff with resources is just half the work for executive leadership. Governing boards should be invested in guides (ACCT, 2020) and professional learning opportunities to ensure new and revised policies and procedures are reviewed with an equity lens. Additionally, executive leadership teams should be actively involved in national organizations that promote data-informed and evidence-based decision making with disaggregated data (AACC, n.d.; Achieving the Dream, n.d.; Garder Institute, n.d.). Data should expand beyond the classroom to include co-curricular, support services, and post-graduation information.

National faculty associations have created visions (e.g., the American Association of Colleges and Universities (AAC & U, 2018) A Vision for Equity), series (e.g., the Mathematical Association of America’s Equity in Action (2022)), networks (e.g., the National Organization for Student Success’ Equity, Access and Inclusion Network (n.d.)), and position statements (e.g., AMATYC’s Diversity, Equity and Inclusion statement (2020)) focused on equity in the transformation of curriculum, pedagogy/andragogy, and support services. Administration needs to support faculty participation in organizations such as these, bolster professional development resources, and incentivize localized research. Faculty ownership of the transformed learning environment requires a commitment from administration to support professional learning, innovative practices, and continuous improvement models. These continuous improvement models must take on a collaborative approach to move the needle on equity gaps; mathematics faculty cannot do it alone. Institutional research, faculty in other disciplines, student affairs, and academic support departments are all critical to both increasing student success and achieving equitable student outcomes.

Institutions support students through many departments and programs that rely on the expertise of educators serving in staff roles. Staff facilitate and coordinate institutional operations, including registration, financial aid, and tutoring. The multitude of roles that staff utilize to effect change and to implement equitable practices provide them with a unique capacity to change our institutions. Staff support our institutions’ equity missions through student support services, hiring practices, and collaboration with faculty and local schools.

Change must happen individually before it can happen collectively. People drive change, lead change, and sustain change. Lasting change happens when educators understand both the meaning of equity and that meaning is represented through personal values, beliefs, and actions. (McNair et al., 2020, p. 1)

The Institution’s Role in Evidence-Based Practices

To make an impact on student success in the first two years of college mathematics will require faculty to view mathematics education through an equity lens (Kezar et al., 2020; Lin et al., 2020; Purnell & Burdman, 2022). To support faculty in viewing efforts through an equity lens, it is imperative that institutions provide support in terms of available evidence. The data provided must be aggregated and disaggregated, showing a clearer picture of the intricacies in the data. Equally important, the institution must seek out and make available qualitative data to inform faculty on the student experience. Both ownership and engagement are PROWESS Pillars (AMATYC, 2018, p. 9) and cannot be fully measured without speaking to and understanding the student experience. Finally, and most importantly, the institution must create a culture that supports data use as a tool for improvement, not as an instrument of fault finding. (See also Chapter 6, pp. 57-60.)

As stated in the AMATYC (2020) statement on Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in Mathematics, “Equity reform in mathematics teaching requires institutional change, such as … collect data that is disaggregated, longitudinal and includes quantitative and qualitative components” (para. 4).

Collecting the data does not, by itself, create a more equitable environment for the teaching of mathematics. The institution must also create an environment that allows and encourages faculty to ask questions about the data, investigate the causes of disparities in the data, and act upon their conclusions. As seen in AMATYC’s (2018) IMPACT, there is no “average” student in the community college. Each institution will have unique needs based on the population of students. This also means that honest discussions around the current success and difficulties of marginalized populations must occur (Diggles, 2014). This will only happen when faculty operate in a culture that encourages and promotes the deep understanding and questioning of data (Hora et al., 2017).

Active and Collaborative Learning

Incorporating diversity and inclusion into active learning is essential for creating an equitable and supportive educational environment. Active learning strategies engage students in the learning process and can be enhanced to promote diversity and inclusion. When researching active learning or collaborative learning, instructors will find various definitions. We will define active learning as learning that allows for students to be engaged in their learning process as opposed to passive learning (such as lecture-based). Likewise, we will define collaborative learning as using groups of two or more students to share in the learning process.

Integrating active learning in mathematics classrooms involves replacing the traditional lecture model with one that supports productive student interactions (Boyce & O’Halloran, 2020). A study by Theobald et al. (2020) found that the amount of active learning students perform in a STEM classroom positively correlates with narrowing achievement gaps between students in minoritized groups and non-minoritized groups. It should be noted that active learning in the classroom reconstructs the instructor’s role to that of a facilitator of student’s educational development. The interaction between the instructor and student is productive and relies on each class session’s context (Lombardi et al., 2021). Theobald et al. (2020) noted that this does not mean that lecturing is not an effective form of instruction; however, lecture alone will not deepen most students' understanding in STEM. Lombardi et al. (2021) stated that it is important to ensure that when incorporating lecture with active learning activities, it must be implemented to increase student action in knowledge development and meaning building.

Active learning in the mathematics classroom also involves collaborative learning. According to Ching (2020), collaborative learning allows students the opportunity to be more actively engaged in their learning or task and hence helps them understand the material more efficiently. The author furthermore states that collaborative learning has also shown that students who tend to perform below average become more capable in their education. Ching (2020) discussed a study in which collaborative learning techniques were implemented in a college mathematics class. It was found that students who were typically less engaged in solving mathematics problems became more diligent in working on their mathematics exercises when given the opportunity to work with other classmates. These students also increased their cognitive and social skills through working with fellow students.

Student-to-student and instructor-to-student interaction is important for positive effects on students’ learning in the classroom. Lugosi and Uribe (2022) found that when the instructor gives feedback and encouragement during active learning activities, this can have an improvement in students’ emotional intelligence. The authors also discovered that allowing students to work in groups, engage in class presentations, and have opportunities to explore and experiment in their mathematics class will result in students being engaged in problem solving and mathematical inquiry. In fact, students are more apt to connect current mathematics knowledge to previous knowledge by engaging in active learning activities in the classroom and hence increase their likelihood of storing this new knowledge into their long-term memory.

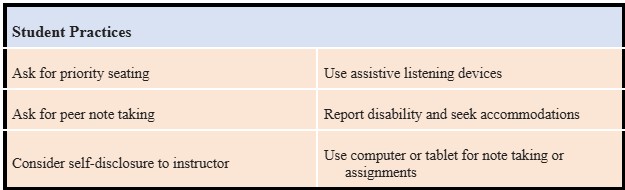

What about microaggressions that may occur in the classroom during an active learning activity? How can the instructor respond to possible microaggressions? Souza (2018) created a communication framework on how we can respond to microaggressions in the classroom called ACTION. Implementing these strategies in your classroom can help address and even reduce microaggressions in the classroom.

Figure 1. Taking ACTION against microaggressions during active learning (Souza, 2018).

Active learning has been gaining momentum in higher education. Many colleges are researching the effectiveness of implementing active learning strategies in the classroom. Collaborative learning works hand in hand with active learning activities to help students work with their peers and help each other in their learning process. By implementing active learning techniques in the classroom, students can become more engaged in their work and their education journey.

Examples of active and collaborative learning:

-

Whole group discussions.

-

Online collaboration spaces (such as Teams or Zoom)

-

Think/Pair/Share.

-

Class polls (such as Kahoot or Jotform).

-

Group projects (collaborative learning).

-

Class games to review material (such as Jeopardy or Bingo).

-

Multiple small groups working on problems together at the board.

In an inclusive mathematics college classroom, active learning takes center stage as a dynamic and equitable pedagogical approach. Here, students of diverse backgrounds and abilities actively engage in the learning process through collaborative problem solving, group discussions, and hands-on activities. This approach fosters an inclusive environment where all voices are heard and valued, enabling students to acquire mathematical knowledge and develop critical thinking skills, boost self-confidence, and appreciate the richness of different perspectives. Instructors create a supportive space where students feel empowered to explore mathematical concepts together, breaking down barriers and ensuring that all learners have an opportunity to thrive in the world of mathematics. (See also Chapter 5, p. 44.)

Universal Design

Students experiencing life-long or temporary physical, psychological, or mental impairments are human beings who add to the diverse cultural mix of society and contribute to our society in all the unique ways that each other member of society does. Such differences include, but are not limited, to visual, speech, mobility, dexterity, and hearing impairments; intellectual disabilities; major depressive disorders, emotional illnesses, post-traumatic stress disorders, traumatic brain injuries, and specific learning disabilities, such as autism, ADD, and ADHD; cerebral palsy; epilepsy; muscular dystrophy; multiple sclerosis; orthopedic conditions; cancer; heart disease; diabetes; and contagious and noncontagious diseases, such as tuberculosis and HIV disease (whether symptomatic or asymptomatic). These disabilities or differences can be invisible or visible.

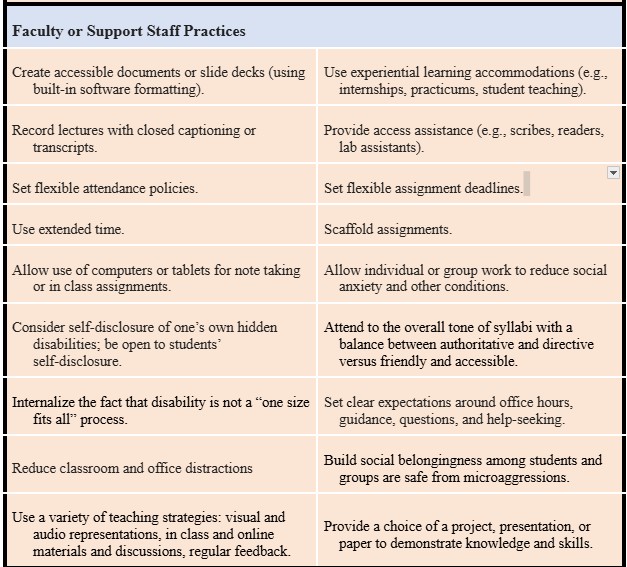

Figure 2. Community college students with disabilities, 2015–2016 (AACC, 2018).

The National Center for Educational Statistics (NCES, 2022) reports that 13% of the students at community colleges have reported disabilities to their institutions, however, NCES data further suggests that only 37% of the students with disabilities do inform their institutions (Key Findings, Informing). Our population of students with disabilities is large—close to one third of students with disabilities attend community colleges. Figure 2 identifies the major categories of reported disabilities at community colleges.

Fostering equity and inclusion demands that we acknowledge the need for implementing the principles of universal design into our programs and curriculum. Universal design for learning, as developed by CAST, is a framework to improve and optimize teaching and learning for all people, based on scientific insights into how humans learn. It is useful to consider the social model of disability. Society has moved from a medical model (treating the individual to fit) to a more inclusive social model (how we arrange society to be inclusive) with respect to abilities. The disabilities that are experienced in the classroom or on campus are there because the environmental framework was built to benefit physically, mentally, and psychologically able-bodied persons. It was a choice. We can instead grow a more humane society, and embrace and choose inclusivity.

Faculty can promote disability justice and reduce ableism through the inclusion of equitable teaching and learning practices, such as disability accommodations and inclusive course design strategies. Through these practices, barriers can be reduced and, in some cases, entirely removed for students with disabilities. Disability accommodations focus on meeting the individual needs of the student by requesting modifications to the learning environment. By setting up proactive strategies to create courses and support services that are accessible to the widest variety of students, institutions, faculty, and staff may reduce the need for some individualized disability accommodations. One example would be reducing timed assessments. Extended time on tests as an accommodation should also be considered as part of universal design. Timed tests in mathematics have been shown to heighten anxiety in some students while lowering their overall exam performance (Stretch & Osborne, 2019). The authors also discuss how extended time on tests can be beneficial for most students. In fact, Gernsbacher et al. (2020) delve into the inequitable and exclusive nature of timed tests as evidenced in studies and propose the subsequent recommendations:

-

Remove time limits on all tests.

-

If time is limited due to class constraints, consider administering the test asynchronously (such as online or take home).

-

Consider assigning projects, reflections, and other alternative types of assessments to assess mastery in addition to traditional testing.

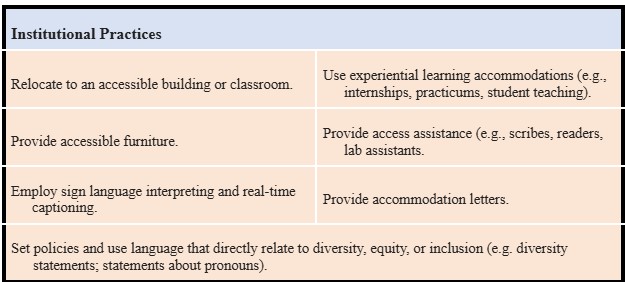

Designing assessments that are not time bound or use less than one quarter of the classroom time (so that students needing additional time would be naturally accommodated within the classroom time structure) would be an appropriate accommodation to the social structure, reducing the medical model of exceptions for individuals. As part of envisioning a more inclusive society, instructors and support staff need to center the students’ needs. Accommodations do not change the expectations of students to meet essential requirements or learning outcomes of a course, service, or program, though essential requirements may need to be evaluated and modified if they are bound by a particular mobility, physical, or dexterity ability. For example, does every student need to graph an equation without technology, or is the course requirement to know the characteristics of types of graphs and to recognize those characteristics? See Table 1 for examples of accommodations that can be promoted at the institutional, faculty or staff, or student level. (See Chapter 4, pp. 37–39 for more information.)

Table 1

Institutional, Faculty or Support Staff, and Student Practices

Developing and implementing a teaching practice based on universal design may seem like a monumental undertaking, but small steps and incremental changes can make a big difference (Boysen, 2021; Dahlstrom-Hakki & Wallace, 2022; Duranczyk & Fayon, 2008; Izzo et al., 2010; Kachwalla, 2021; La et al., 2018; Lambert et al., 2021; Penner, 2018). Universal design for learning takes into consideration assessments, pedagogy, and communications. These considerations reduce students’ need for individualized accommodations and can benefit all learners, not just the students with disabilities. The following list includes some resources to get started.

Working Together for Equity and Inclusion

This chapter highlights the benefits of equity and inclusion within our college mathematics classrooms. It recognizes that our diverse student body brings with it a wealth of perspectives, talents, and experiences. By promoting fairness and accessibility, we ensure that every student has the opportunity to thrive mathematically, irrespective of their background.

Every student is a valued member of the educational community, irrespective of background or identity. The best path forward in mathematics education is to recognize that the success of all students is of paramount importance, but it is a multifaceted issue without a quick fix. Mathematics education must look beyond the content and to the student. Helping students feel a sense of belonging in the classroom, being aware of our own biases, and adopting universal design are three critical aspects of supporting student success. We encourage faculty to become leaders in this ripple of change that creates supportive environments for all students to learn.

Faculty are at the heart of student success. They are directly responsible for delivering content and connecting to students. “It’s their passion, hard work and authentic interactions that help” students succeed (Malvik, 2020, para. 1). Faculty develop and deliver the mathematics curriculum and, therefore, have the responsibility and discretion to select the educational experiences encouraged in the classroom (U.S. DoE, 2016). Many well-established frameworks foster pedagogical engagement with access and inclusion, incorporating students with disabilities, as well as other populations that have experienced marginalization in our society; examples include antiracist pedagogy, multicultural education, and inclusive pedagogy. Regardless of the approach, accessible and inclusive teaching is guided by these seven grounding principles (Carter, 2022):

-

Integrate diversity: Establish guidelines that capitalize on difference as inherently valuable by including and supporting diverse voices throughout the course in reading materials, research cited, visuals presented, and all course and classroom artifacts. (See Chapter 3, p. 25.)

-

Expand access: Identify the key skills necessary for achieving course goals and proactively consider accessibility to reduce the need for reactive or retroactive adjustments throughout the semester.

-

Foster belonging: Design the course with a learning community model, where there are shared responsibilities, being proactive in addressing and interrupting exclusionary social dynamics. (See Chapter 4, p. 33.)

-

Utilize differentiated instruction: Explicitly acknowledge and model multiple instructional practices to reinforce that one approach to teaching and learning does not meet the needs of all students or all instructors. (See Chapter 4, p. 34.)

-

Embrace structured flexibility: Design the course with multiple paths to achieve course goals and alternative plans, as changes in structure may enhance both students’ and instructors’ performances. (See Chapter 7.)

-

Model transparency: Be explicit in clearly presenting, describing, and detailing learning objectives, essential requirements, and pedagogical choices to enhance students’ understanding of teaching and learning decisions.

-

Incorporate feedback: Create opportunities for reflection, feedback, and revision within assignments and in the overall course design, so personal and shared reflections can inform the teaching and learning practices throughout the semester. (p. 2)

Institutions are responsible for ensuring faculty are supported and provided with resources and professional development opportunities, not leaving faculty to work alone. Only by engaging and supporting faculty as a community of practitioners, and by fostering the willingness to question long-held beliefs, will the ripple continue to grow. Institutions must hire faculty who are credentialed and highly knowledgeable about teaching and learning theories for mathematics and who can bring diverse perspectives and differing views to the classroom (AMATYC, 2018). Through this diversity, students gain unique perspectives on mathematics, classroom interactions, college, and life. Institutions must focus on who is in the classroom to ensure students succeed in their first two years of college mathematics.

Faculty are responsible for exploring their own implicit biases, learning how to address microaggressions in and out of the classroom, and supporting students who may be experiencing stereotype threat. By utilizing pedagogical techniques, such as active and collaborative learning, and designing courses with a more universal design, faculty can improve the college experience of students and increase student success. Diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility should be critical aspects of any classroom experience, curriculum development, pedagogy, hiring process, retention policy, and professional development program. When institutions, faculty, and staff collaborate to address these issues together, we can build stronger, more effective programs and positively impact student success.

References

Achieving the Dream. (n.d.). Transforming colleges, transforming communities. https://achievingthedream.org/

American Association of Colleges and Universities (AAC & U). (2018). A vision for equity. https://www.aacu.org/publication/a-vision-for-equity

American Association of Community Colleges (AACC). (2017). AACC pathways: Building capacity for reform at scale in the community college field. https://www.aacc.nche.edu/programs/aacc-pathways-project/

American Association of Community Colleges (AACC). (2018). Students with disabilities. Data Points, 6(13). https://www.aacc.nche.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/DataPoints_V6N13.pdf

American Association of Community Colleges (AACC). (n.d.). What is the VFA? Voluntary Framework of Accountability. https://vfa.aacc.nche.edu/about-vfa/

American Mathematical Association of Two-Year Colleges (AMATYC). (2018). IMPACT: Improving mathematical prowess and college teaching. https://cdn.ymaws.com/amatyc.site-ym.com/resource/resmgr/impact/impact2018-11-5.pd f

American Mathematical Association of Two-Year Colleges (AMATYC). (2020). Position statement of the American Mathematical Association of Two-Year Colleges: Diversity, equity, and inclusion in mathematics. https://amatyc.org/page/PositionDiversityEquityInclusion

Applebaum, B. (2019). Remediating campus climate: Implicit bias training is not enough. Studies in Philosophy & Education, 38(2), 129–141. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11217-018-9644-1

Association of Community College Trustees (ACCT). (2020). Diversity, equity & inclusion: A checklist and implementation guide for community college boards. https://www.acct.org/publications-media/reports-and-papers/diversity-equity-and-inclusio n-2020

Boyce, S., & O’Halloran, J. (2020). Active learning in computer-based college algebra. PRIMUS, 30(4), 458-474. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511970.2019.1608487

Boysen, G. A. (2021). Lessons (not) learned: The troubling similarities between learning styles and universal design for learning. Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology, 1-15. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/stl0000280

Carter, A. M. (2022). Teaching with access and inclusion. Minnesota Transform and the Center for Educational Innovation, University of Minnesota. https://z.umn.edu/TAI

Casanova, S., McGuire, K. M., & Martin, M. (2018). “Why you throwing subs?”: An exploration of community college students’ immediate responses to microaggressions. Teachers College Record, 120(9), 1-48. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146811812000901

Ching, D. A. (2020). Two cubed approach in a collaborative classroom and the enhanced algebra and social skills of college students. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 8(10), 4920-4930. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujer.2020.081064

Dahlstrom-Hakki, I., & Wallace, M. L. (2022). Teaching statistics to struggling students: Lessons learned from students with LD, ADHD, and autism. Journal of Statistics and Data Science Education, 30(2), 127-137. https://doi.org/10.1080/26939169.2022.2082601

Dana Center. (n.d.). Mathematics pathways: The right math at the right time for each student. http://www.dcmathpathways.org/

Diggles, K. (2014), Addressing racial awareness and color-blindness in higher education. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 2014(140), 31-44. https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.20111

Duranczyk, I. M., & Fayon, A. K. (2008). Successful undergraduate mathematics through universal design of essential course components, pedagogy, and assessment. In J. L. Higbee & E. Goff (Eds.), Pedagogy and student services for institutional transformation: Implementing universal design in higher education (pp. 137-153). University of Minnesota.

Gardner Institute. (n.d.). Lead every student to graduation—And your institution to lasting growth. https://gardnerinstitute.org/

Gernsbacher, M. A., Soicher, R. N., & Becker-Blease, K. A. (2020). Four empirically based reasons not to administer time-limited tests. Translational Issues in Psychological Science, 6(2), 175-190. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/tps0000232

Grossman, J. M., & Porche, M. V. (2014). Perceived gender and racial/ethnic barriers to STEM success. Urban Education, 49(6), 698-727. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085913481364

Hora, M. T., Bouwma-Gearhart, J., & Park, H. J. (2017). Data driven decision-making in the era of accountability: Fostering faculty data cultures for learning. The Review of Higher Education, Project MUSE, 40(3), 391-426. https://doi.org/10.1353/rhe.2017.0013.

Izzo, M. V., Rissing, S. W., Andersen, C., Nasar, J. L., & Lissner, L. C. (2010). Universal design for learning in the college classroom. In W. F. E. Preiser & K. H. Smith (Eds.), Universal design handbook (2nd ed., p. 39.1-39.6). McGraw-Hill.

Jenkins, D., Lahr, H., Brown, A. E., & Mazzariello, A. (2019). Redesigning your college through guided pathways: Lessons on managing whole-college reform from the AACC Pathways Project. Community College Research Center. https://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/publications/redesigning-your-college-guided-pathways.html

Jobs for the Future. (2016). Meta-Majors: An essential first step on the path to college completion. https://archive.jff.org/resources/meta-majors-essential-first-step-path-college-completion/

Kachwalla, B. (2021). Making math accessible to all students: Effective pedagogy? Journal of Higher Education Theory and Practice, 21(3), 89-95. https://articlearchives.co/index.php/JHETP/article/view/2899

Kezar, A., Holcombe, A., Vigil, D., & Dizon, J. P. M. (2021) Shared equity leadership: Making equity everyone’s work. American Council on Education; University of Southern California, Pullias Center for Higher Education.

La, H., Dyjur, P., & Bair, H. (2018). Universal design for learning in higher education. Taylor Institute for Teaching and Learning. Calgary: University of Calgary.

Lambert, R., Imm, K., Schuck, R., Choi, S., & McNiff, A. (2021). “UDL is the what, design thinking is the how:” Designing for differentiation in mathematics (EJ1321118). ERIC. Mathematics Teacher Education and Development, 23(3), 54-77. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1321118.pdf

Lewis, K. L., Stout, J. G., Pollock, S. J., Finkelstein, N. D., & Ito, T. A. (2016). Fitting in or opting out: A review of key social-psychological factors influencing a sense of belonging for women in physics. Physical Review Physics Education Research, 12(2), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevPhysEducRes.12.020110

Lin, Y., Fay, M. P., & Fink, J. (2020). Stratified trajectories: Charting equity gaps in program pathways among community college students (ED610667). ERIC. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED610667.pdf

Lombardi, D., Shipley, T. F., Bailey, J. M., Bretones, P. S., Prather, E. E., Ballen, C. J., Knight, J. K., Smith, M. K., Stowe, R. L., Cooper, M. M., Prince, M., Atit, K., Uttal, D. H., LaDue, N. D., McNeal, P. M., Ryker, K., St. John, K., van der Hoeven Kraft, K. J., & Docktor, J. L. (2021). The curious construct of active learning. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 22(1), 8-43. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100620973974

Lugosi, E., & Uribe, G. (2022). Active learning strategies with positive effects on students’ achievements in undergraduate mathematics education. International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology, 53(2), 403-424. https://doi.org/10.1080/0020739X.2020.1773555

Malvik, C. (2020). Acknowledging the importance of faculty training and development. https://collegiseducation.com/insights/enrollment-growth/importance-of-faculty-trainingand-development/

Master, A. H., & Meltzoff, A. N. (2020). Cultural stereotypes and sense of belonging contribute to gender gaps in STEM (ED605235). ERIC. International Journal of Gender, Science and Technology, 12(1), 152-198. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED605235.pdf

Mathematical Association of America. (2022). Conversations for the math community: Equity in action [Webinar series]. http://info.maa.org/pages/1780913/23513

McNair, T. B., Bensimon, E. M., & Malcom-Piqueux, L. (2020). From equity talk to equity walk: Expanding practitioner knowledge for racial justice in higher education. John Wiley & Son. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119428725

National Center for Educational Statistics (NCES). (2022, April 26). A majority of college students with disabilities do not inform school, new NCES data show [Press release]. https://nces.ed.gov/whatsnew/press_releases/4_26_2022.asp

National Organization for Student Success. (n.d.). Equity, access and inclusion network. https://thenoss.org/EAI-Network

Ogunyemi, D., Clare, C., Astudillo, Y. M., Marseille, M., Manu, E., & Kim, S. (2020). Microaggressions in the learning environment: A systematic review. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 13(2), 97-119. https://doi.org/10.1037/dhe0000107

Penner, M. R. (2018). Building an inclusive classroom. Journal of Undergraduate Neuroscience Education, 16(3), A268-A272. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6153021/

Purnell, R. D., & Burdman, P. (2022). Solving for equity in practice: New insights on advancing college opportunity and success. Notices of the American Mathematical Society, February, 249-251. https://www.ams.org/journals/notices/202202/rnoti-p249.pdf

Rainey, K., Dancy, M., Mickelson, R., Stearns, E., & Moller, S. (2018). Race and gender differences in how sense of belonging influences decisions to major in STEM. International Journal of STEM Education 5(10), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-018-0115-6.

Rizki, L. M., & Priatna, N. (2019). Mathematical literacy as the 21st century skill. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1157(4), 042088. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1157/4/042088

Solórzano, D., Ceja, M., & Yosso, T. (2000). Critical race theory, racial microaggressions, and campus racial climate: The experiences of African American college students. Journal of Negro Education, 69(1/2), 60-73. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2696265

Souza, T. (2018, April 30). Responding to microaggressions in the classroom: Taking ACTION. Faculty Focus. https://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/effective-classroom-management/responding-to-m icroaggressions-in-the-classroom/

Staats, C. (2015/2016). Understanding implicit bias: What educators should know. American Educator, 39(4), 29-33, 43.

Stretch, L. S., & Osborne, J. (2019). Extended time test accommodation: Directions for future research and practice. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, 10(1), article 8. https://doi.org/10.7275/cs6a-4s02

Sue, D. W. (2010). Microaggressions in everyday life: Race, gender, and sexual orientation. Wiley.

Sue, D. W., Alsaidi, S., Awad, M. N., Glaeser, E., Calle, C. Z., & Mendez, N. (2019). Disarming racial microaggressions: Microintervention strategies for targets, White allies, and bystanders. American Psychologist, 74(1), 128-142. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000296

Sue, D. W., Capodilupo, C. M., Torino, G., C., Bucceri, J. M., Holder, A. M. B., & Nadal, K. L. (2007). Racial microaggressions in everyday life: Implications for clinical practice. American Psychologist, 62(4), 271-286. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.62.4.271

Souza, T. (2018). Responding to microaggressions in the classroom: Taking ACTION. Faculty Focus: Higher Ed Teaching & Learning. https://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/effective-classroom-management/responding-to-m icroaggressions-in-the-classroom/

Theobald, E. J., Hill, M. J., Tran, E., Agrawal, S., Arroyo, E. N., Behling, S., Chambwe, N., Cintrón, D. L., Cooper, J. D., Dunster, G., Grummer, J. A., Hennessey, K., Hsiao, J., Iranon, N., Jones II, L., Jordt, H., Keller, M., Lacey, M. E., Littlefield, C. E., ... & Freeman, S. (2020). Active learning narrows achievement gaps for underrepresented students in undergraduate science, technology, engineering, and math. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(12), 6476-6483. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.191690311

U.S. Department of Education (U.S. DoE). (2016). Advancing diversity and inclusion in higher education: Key data highlights focusing on race and ethnicity and promising practices.. https://www.acha.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/advancing-diversity-inclusion.pdf

Williams, M. T., Kanter, J. W., Peña, A., Ching, T. H. W., & Oshin, L. (2020). Reducing microaggressions and promoting interracial connection: The racial harmony workshop. Journal of Contextual and Behavioral Science, 16, 153-161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2020.04.008